Thinking and Working Politically (TWP) has been a game changer for development practitioners. Whether it is through applied Political Economy Analysis, Gender Analysis, or Systems Mapping, TWP is a vast suite of methodologies to guide activity implementation in complex contexts where political, economic, and social dynamics are rapidly evolving. In these contexts, knowing which actors to engage and which windows of opportunity to leverage not only ensure programmatic success, but can also make the critical difference when considering risk and do no harm principles.

Considering the growing popularity and applicability of TWP, Counterpart International has been exploring how to ensure that it can enable local stakeholders to advocate more effectively for change. To date, TWP has largely remained an approach used by donors and implementers to meet their needs for improved program design and implementation. For TWP to remain relevant in the “journey to self-reliance” era, it needs to shift its focus to generating local knowledge that empowers local actors and supports their strategies and agendas for change.

As part of its recently launched Inclusive Social Accountability (ISA) framework, Counterpart International is proposing another way to think and work politically – by adding a layer of inclusivity. ISA’s first Building Block focuses on operationalizing and localizing knowledge gathered through TWP approaches. In the framework, TWP serves a dual purpose: first, it supports program design and evaluation. Second, it drives greater stakeholder awareness and incentivizes collaboration among stakeholders. Most importantly our proposed approach aims to ensure that stakeholders have ownership of the knowledge created in the process and can use it to design their own local solutions and strategies. This is why we call it

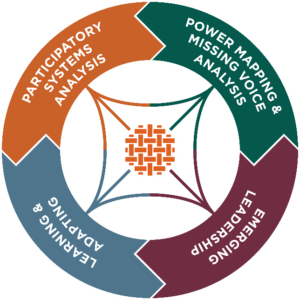

Stakeholder-Driven TWP. It revolves around four core elements as illustrated below:

- Participatory Systems Analysis: we conduct participatory action-oriented research by bringing stakeholders together to map out systems and decision-making processes.

- Through power mapping and missing voice analysis we work with stakeholders to understand power dynamics and identify emerging alliances as well as drivers of change and resistance. We focus on identifying groups that have been excluded from formal processes and develop inclusion strategies.

- Next, we work with traditionally excluded groups to identify existing and emerging leadership and facilitate their effective participation in decision-making processes.

- Finally, using CLA approaches we engage stakeholders in learning and adapting activities, so they can adjust their strategies for inclusive social change.

In Niger, where Counterpart is implementing the Participatory Responsive Governance program (PRG-PA) we have used participatory system and power mapping to promote change in the Teacher Management System (TMS), a system that had been identified as a bottleneck to improving quality, inclusion, and accountability in education. Following extensive consultations with key stakeholders, Counterpart drafted a power map and used it as a tool to facilitate dialogue and promote awareness and collaborative problem-solving among the different stakeholders. The process led to a comprehensive redeployment of teachers nationally, including 320 teachers redeployed in the three regions where PRG-PA is operating (Zinder, Agadez, and Diffa).

The power mapping exercise was successful because it brought stakeholders together to discuss and collaborate, resulting in several benefits: first, it helped refine and adapt the map to different localities. Second, it improved stakeholder understanding of how the Teacher Management System works. Third, it provided a stage for stakeholders to discuss how the system could be improved and helped shape a consensus around needed reform. Finally, the process helped distinguish between stakeholders that supported reforms, were undecided, and those who remained categorically opposed. This third category included opponents who had formally “supported” reform but whose vested interests in maintaining the status quo became clear through the process. To help scale up the power mapping approach and create more local knowledge, Counterpart now works with local partners to build their capacity to conduct political economy analyses and more generally think and work politically.

This is just one example that demonstrates how TWP can be done differently, pointing to a way forward from development practitioners thinking and working politically on behalf of local actors towards stakeholder-driven TWP. In the process, we assist in the creation of powerful local knowledge that will be used locally to achieve lasting change and foster increased self-reliance.